![]() For Black History Month, I’ve been reading about the impact that African American parents and self-advocates have had on both racial desegregation and disability rights. One mother I keep thinking about is Lucille Bridges, whose brave young daughter Ruby was immortalized by Norman Rockwell after she became the first African American child to attend her Louisiana school in 1954.

For Black History Month, I’ve been reading about the impact that African American parents and self-advocates have had on both racial desegregation and disability rights. One mother I keep thinking about is Lucille Bridges, whose brave young daughter Ruby was immortalized by Norman Rockwell after she became the first African American child to attend her Louisiana school in 1954.

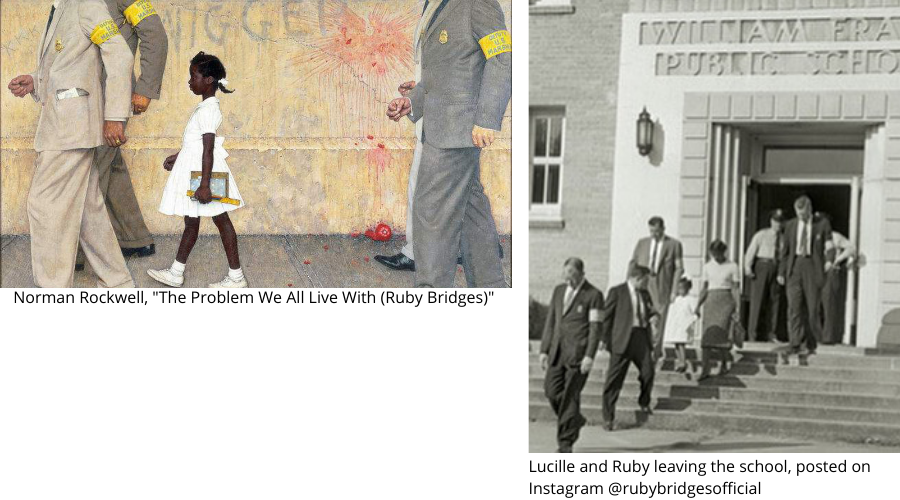

The perspective in Rockwell’s painting is child-level, as Ruby is flanked by the torsos of the National Guardsman who protect her from the mob of racist white protesters. But someone is missing from this powerful image: her mother, Lucille, who walked her to and from school every day.

From a storytelling standpoint, I can understand why Rockwell chose to focus on Ruby’s vulnerability, contrasting her small frame with the tall men in suits and the racist protesters whose bullying is depicted with a tomato thrown against the wall to protest her entry to the school.

As an advocate for family engagement, I feel Lucille’s absence in the photo – because the reality is that young children do not fight for their own Civil Rights. They depend on their parents, families, and communities to fight for them. As a mother of a child with disabilities, I resonate with Lucille’s determination to confront the injustices that threatened to deprive her daughter of an education. And as a white person, I’m in awe of the strength that it took to endure the threats and retaliation that the Bridges family were subjected to by whites who did not want integration to succeed. “Engagement” doesn’t even begin to describe the sacrifices that Lucille and other African American parents have made in the name of educational justice.

Farther beyond the frames of these two images are even more individuals who made Ruby and Lucille’s actions possible. These individuals include their faith community, a therapeutic counselor who offered to help Ruby process her experience, legal advocates and attorneys, local activists and allies, and the elected officials who broke with colleagues in order to put protections in place for the Bridges family.

Ruby Bridges-Hall described her experience to the Tampa Bay Times

This wider community of support is essential to meaningful social change. While many of those in power will fight to hold onto it, some have used their power to help pave the way. For instance, I recently learned about a group of students known as the Claymount Twelve: high schoolers whose parents sued for the right to send them to their local high school instead of a segregated school that was miles away. When Delaware state education officials refused to integrate Claymont High School, the local Superintendent enrolled them anyway – making it the first formerly segregated U.S. school to accept African Americans in 1952. Eventually, their admission was upheld by the State Supreme Court and the case was merged with several others into the landmark case, Brown vs. Board of Education – which outlawed segregation across the U.S. in 1954.

Read more stories behind Brown Vs. Board at The74million.org

These stories bring to light so many themes and lessons. As someone who identifies as white, they remind me of the rights my family has taken for granted and the long struggle for racial justice that continues today. They also fill me with gratitude for the doors that African American activists have opened for other groups to assert their right to be included at school.

Finally, they remind me how easy it is to overlook the role that parents and caregivers play as leaders and partners in the struggle for equity. When schools, community organizations, and families work together toward a shared vision of equal opportunity for all students, the results can be powerful. It might be monumental: dismantling unjust laws and institutions. It might be humble: a teacher and parent unlocking a strategy to help a child learn.

Like an electrical wire, this power is always there. All that’s needed is for schools and agencies to make a connection.